Ancient Egypt: The Bus Wins! Who Knew? More Temples and Padre the Ham

Have you ever been tourist-tired? You know, that point of exhaustion where you’re this close to grumping at someone who doesn’t deserve it (Padre) and you just have to STOP? Squinting into the sun and sticky hot, I headed back to the bus ahead of everyone else to cool off in its calm, air-conditioned silence.

But first, I snapped one last photo before climbing aboard.

I didn’t intend that pic to be of the Gate 1 tour bus at all, but of the glowing pyramids off in the distance. The bus’s bulk served to block a direct sun glare, and despite my jet-lag I marveled at the fact that I was finally here in Egypt, seeing such sites with my very own eyes.

Guess what? That pic won the 40th Anniversary Gate 1 Travel Photo Contest, much to the consternation of Facebook complainers who opined that it was ‘just’ a picture of a bus.

I beg to differ, and I own a snazzy new robot mop* which supports my case. (*Yep, I bought cleaning tools with my winnings. On rare occasions the practical side of me wins out.)

If the contest had been for best photo artistically, I have plenty of others I would have entered.

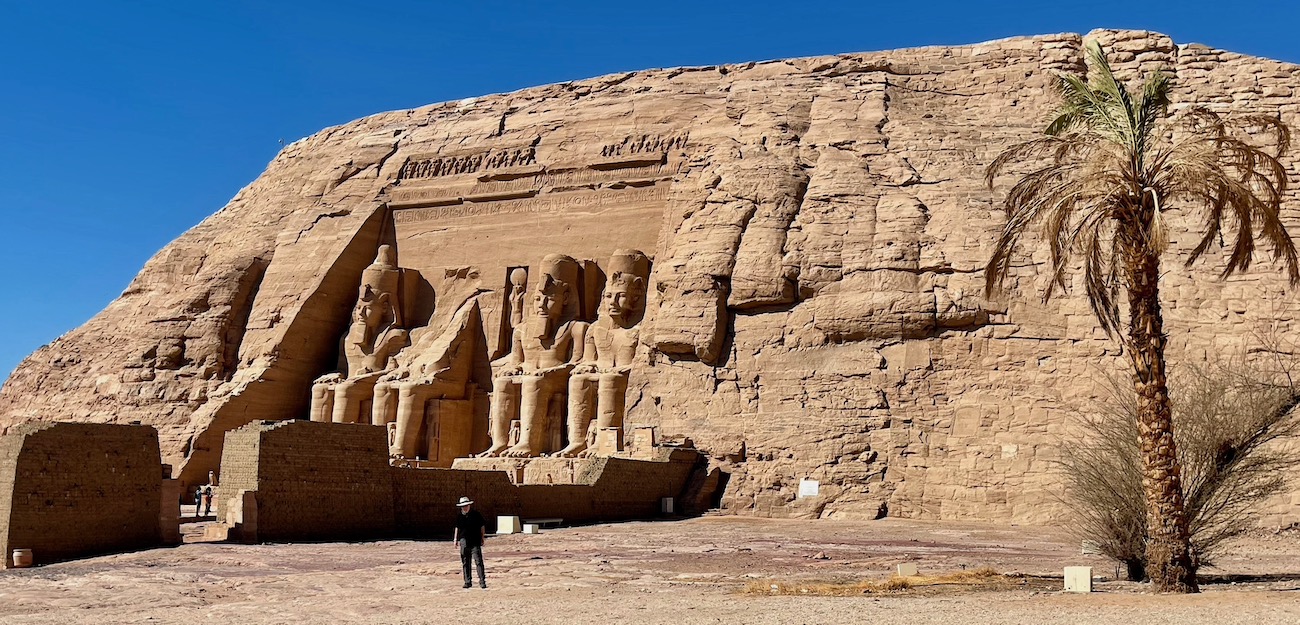

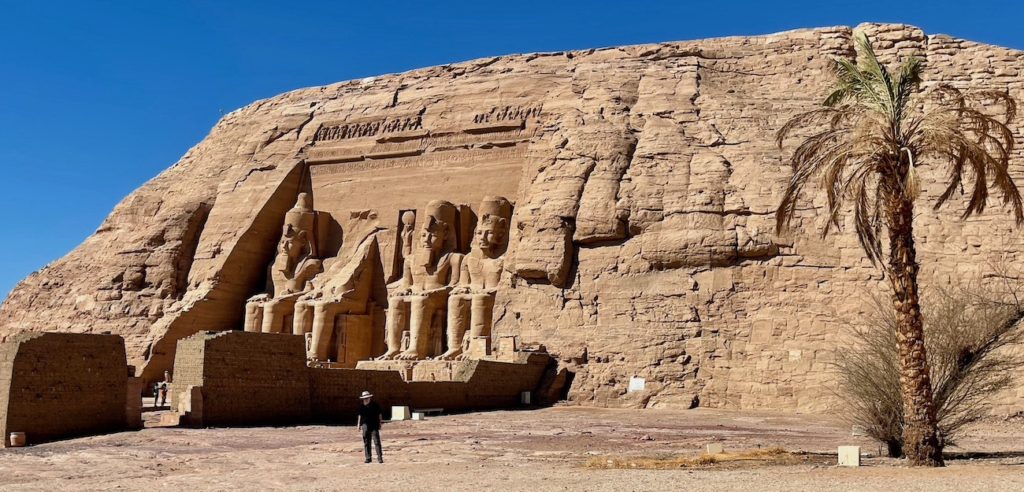

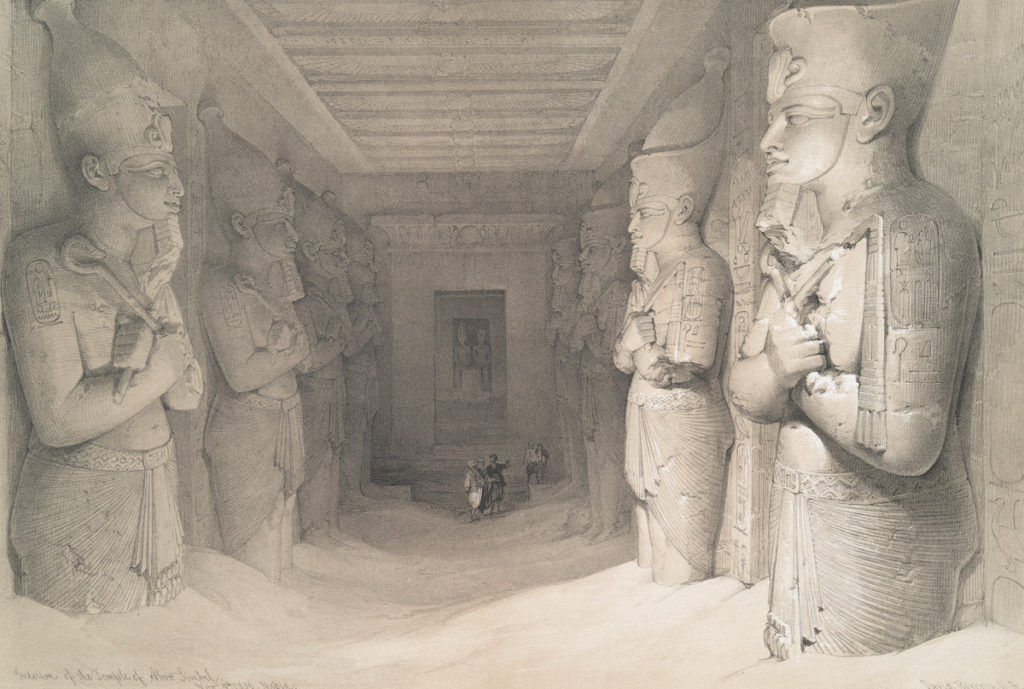

Like this one:

Or this one:

Or maybe this one:

But naw. None of those would have won, even though they’re ‘better’ photos. They just don’t capture the essence of a Gate 1 travel tour. I mean, what is the ONE activity we do the most together, on a tour? We ride the bus of course! Even though we spent seven glorious days of our 13-day tour on a ship, we took plenty of bus rides from the ship, to the ship, to Abu Simbel, to tourist sites further inland, to dinner. The bus served as our classroom, our safe place, our community meeting hall. We bonded on the bus.

So I get it, why they chose my picture. Thank you, Gate 1, and I’ll think of you every time my robot mop chirps into action.

(To see oodles of wonderful travel photos from all over the world, scroll down to the rest of the entries at: Gate 1 Travel Photo Contest 2022.)

RAMSES II’S ABU SIMBEL: ENORMOUS EGO, BUT HE LOVED HIS WIFE

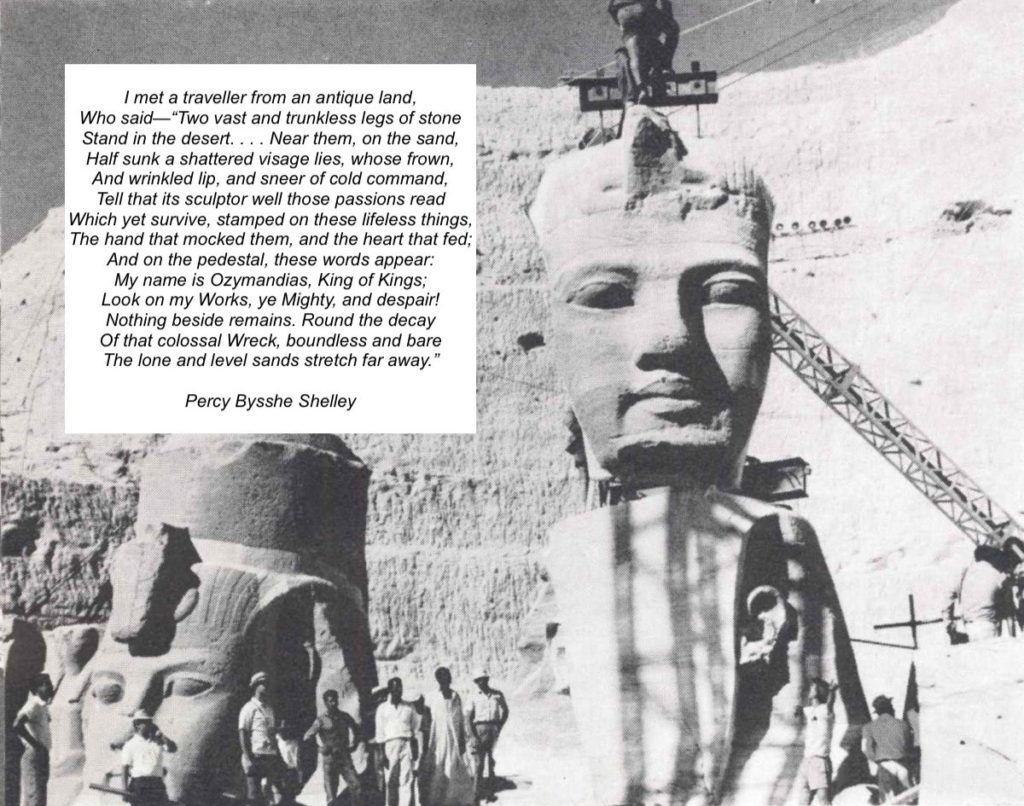

Speaking of bus rides: Remember Ramses II, the guy with the big ego who built massive monuments to himself all over Egypt? Who was the model for the fallen king in the Ozymandius poem, “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair’? That guy? We bumped along on a three-hour sunrise bus ride to get to his masterpiece, Abu Simbel, and it was waaaay worth it – a do-not-miss.

We had stopped in the middle of the desert halfway to Abu Simbel, where barking desert dogs prowled the perimeter of the bus stop. It felt like a high school reunion at first, as tour guides laughed and hugged. Oh duh it WAS a reunion of sorts, since the guides had been out of work for two years, just as our ship crew had been. Abu Simbel tours are now back in business in a big way, yet the bus crowds did not diminish its effect, at least not for us.

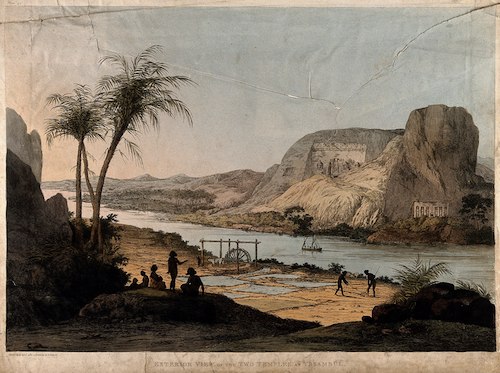

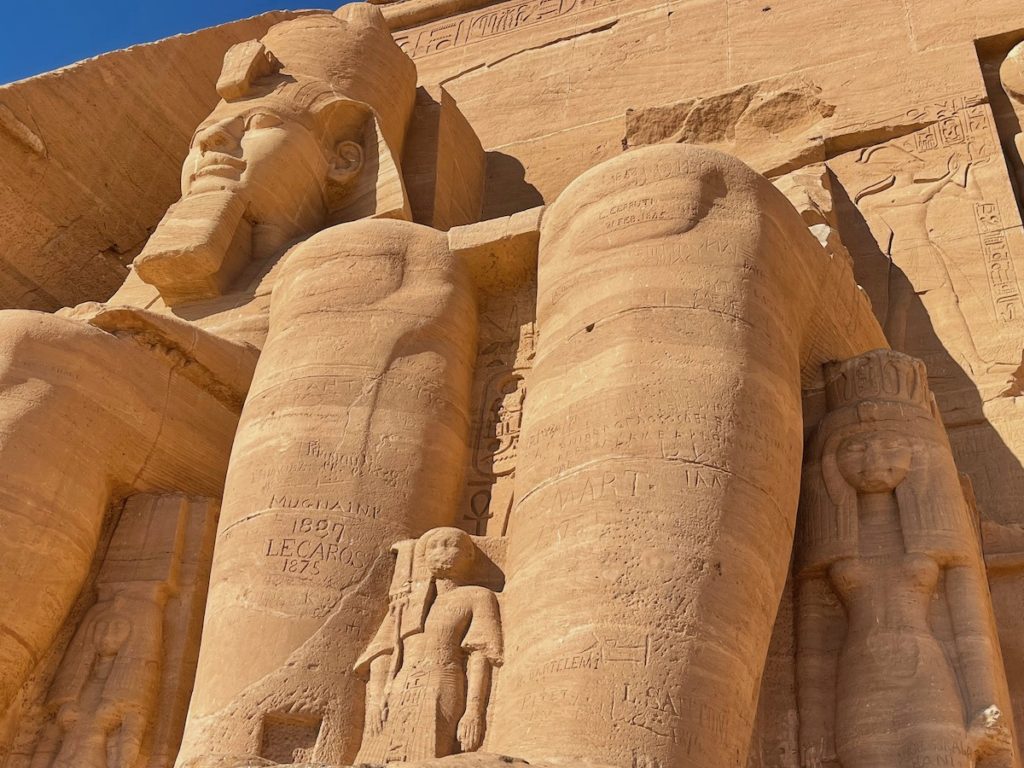

Ramses II outdid himself with these temples, carved into rock cliffs at the southern frontier of pharaonic Egypt, facing Nubia, 12 miles from Sudan’s modern border. Ramses II’s stern statues glared down from the cliffs at river traffic approaching from the south, and warned of what was up ahead, which was nothing good if you happened to be Nubian.

When our guide led us around a corner for the big reveal – Abu Simbel! – I think I said ‘oh wow’ about 20 times. I suspect that ancient Nubians said something similar such as ‘oh crap’ – or however one expressed dismay back in the day. Whatever they said, they had to know that sailing on to Egypt was a bad, bad idea.

Talented stone artisans had rock-cut Ramses II’s 70ft high colossal statues into the sandstone outcrops to terrorize Nubians so they wouldn’t dare think of invading Egypt from the south. Ramses II also declared himself divine, and in the far back of the temple, there he sits with three Egyptian gods.

Temple builders designed things so twice a year, October 22 and February 22, on what is believed to be Ramses coronation and birthday dates, the sun slices through the temple openings to illuminate the four god-statues far in the back. The sun still performs this miracle today, so I have to give Ramses some credit. Or at least give his mathematicians and astronomers credit – those guys were good.

So anyway, big bad Ramses II, who declared himself a GOD, for gosh sakes, frightened everyone who saw this terrifying site into submission. End of story, right? Those Nubians would never DARE invade.

Oh they dared.

Turns out that Ramses’ plan worked at first – a few hundred years maybe, from the time he built them around 1250 BC until 730 BC. By then, though, Ramses II’s isolated river temples had lapsed into disuse, mostly forgotten except by locals who may have picnicked on Ramses II’s nose or whatever.

No longer did the sun’s rays light up Ramses II’s ‘god’ either. Centuries of desert sand blocked temple openings, and massive drifts reached the tops of the statues’ heads. So in 730 BC the Nubian army zipped right past the buried statues, on their way to conquer a weakened Egypt. That successful Nubian invasion of Egypt established the 25th Egyptian Dynasty, the era of the black Pharaohs of Kush.

After that, Abu Simbel stayed lost to the world until 1813, when Swiss explorer Jean-Louis Burckhardt discovered one complete Ramses head sticking up above the sand, with only the headdresses of two other statues barely visible, and another head broken off completely due to an earthquake. And this was before 18th century tourists scratched graffiti all over the statue legs. What a comedown for our guy Ramses II.

I’m not a fan, obviously, due to my fervent distaste for dictators. I did appreciate one thing about him, though: he seemed to be genuinely attached to his chief queen, Nefertari. He built the Small Temple at Abu Simbel in honor of her, as well as the sun goddess Hathor. Dedication text on one of the temple’s buttresses states:

“A temple of great and Mighty monuments, for the Great Royal Wife Nefertari Meryetmut, for whose sake the very sun does shine, given life and beloved.”

So mean old Ramses had a soft side, I guess. That statement is sentimental enough to end up on a Valentine’s card, so the guy might not have been all dictator-bad, I’ll give him that.

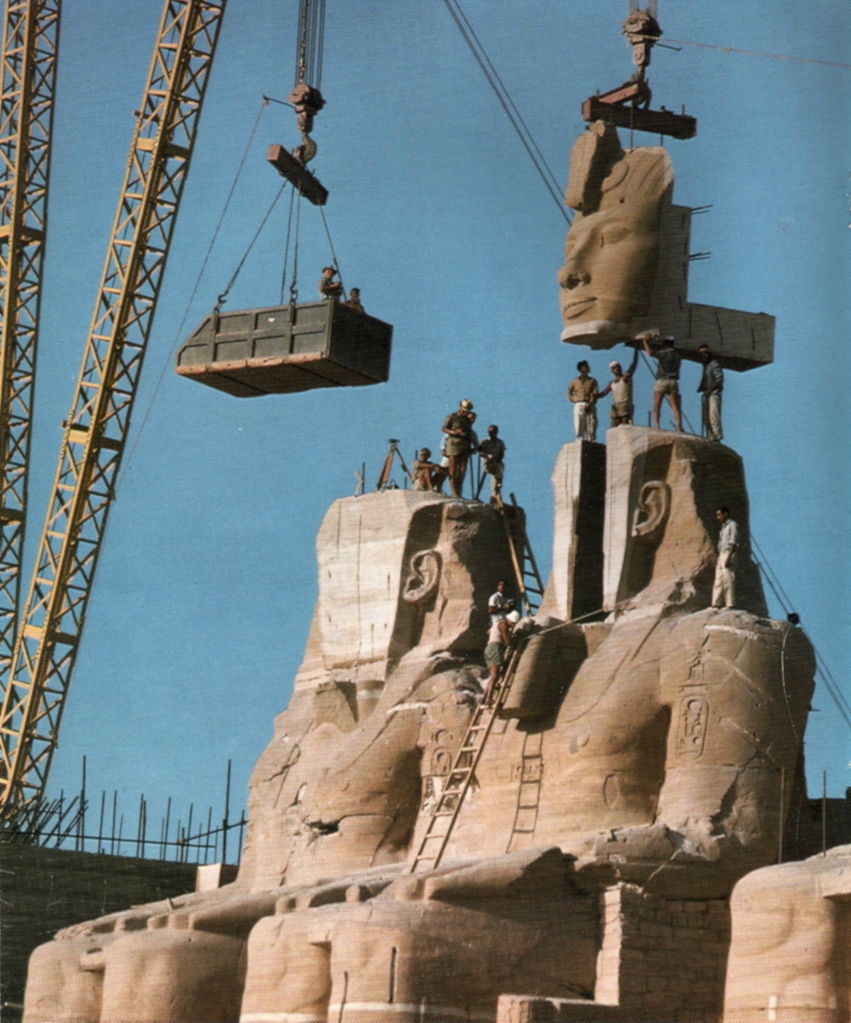

Still, I must point out that dictators don’t last over time; the sun and stone statues do, and only sometimes. In the 1960s, Abu Simbel lasted because talented archeologists and scientists figured out how to move both temples to higher ground to save them from Lake Nasser’s rising waters after the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

Other ancient sites were rescued as well, including Dendur Temple, installed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Some sites couldn’t be saved, though, and now reside below the surface, so only scuba divers can reach them now as they disintegrate under the lake’s waters.

PHILAE TEMPLE: PADRE DIES BUT ISIS (that’s me) SAVES HIM!

Three times we took short trips on the sparkling river in smaller crafts, river birds swooping along in the crisp fresh air around us and swimming children popping up on the rail to sing for tips.

We took in the spectacular view of the famous Cataract Hotel from the river below it, where key scenes in Agatha Christie’s Death On The Nile played out. Christie stayed at the Cataract during winter months while she wrote her murder mystery. I suspect the hotel still looks much the same as it did in the 1930s, when she gazed out its windows conjuring up those convoluted plot twists we mystery readers love so much (she was soooo good at that).

On one motor boat trip we put-putted down the Nile to another temple, Philae, dedicated to the goddess Isis. Expert temple movers had moved Philae Temple to rescue it from rising waters, and we cruised past the tip of the temple’s original island home along the way, steel beams used for the move still peeking up from the river’s depths.

Upon arrival at Philae Temple, Neveen recruited volunteers to help her tell the origin story of the first four Egyptian gods. Padre and I played Isis and her husband Osiris (the ‘good’ gods of life), and the other two volunteers took roles as Osiris’s brother Seti (the ‘bad’ god of death and evil) and Memphis (goddess of compassion). So glad we got good-god roles, but we would have leaned into it in any case, since we both have a bit of play-acting experience in our backgrounds. (Note that I said a ‘bit’.)

It’s a Cain-and-Abel story, where Seti schemes to successfully murder his brother Osiris. Padre played dead perfectly, but I rescued him somehow. Then Seti cuts Osiris up into 14 pieces, scattering his parts throughout the world.

Isis searches the entire kingdom but only finds 13 of the 14 pieces, the 14th being the one so crucial to a man’s fertility. Isis, who does NOT give up (I liked her very much), manages to restore the 14th part by consulting a magician. That’s all I’ll say, except to add that Padre played that part for all it’s worth, to the roar of the crowd (he’s such a ham sometimes, for a quiet guy).

As we toured the rest of the temple, Neveen pointed out how Christians defaced the Egyptian god images, chipping out faces or carving crosses over them. To put the end to idol worship, ancient Christians committed massive art destruction on whatever they could reach, as Egypt’s pharaohs faded away into history.

A GREAT PLACE FOR KIDS: OUR VISIT TO A PEACEFUL NUBIAN VILLAGE

Later that afternoon, we took another motor boat ride down the river to a cliffside Nubian village, where residents hosted us for drinks in a sprawling home complex perched high above the river with spectacular views. Due to its location, this village wasn’t moved after the construction of the Aswan High Dam, even though 50,000+ other Nubian villagers were. Thousands lost their homes to the river, a culture-destroying event whose ramifications Egypt still deals with today.

A gracious Nubian gentleman named Noah served as our nature and village guide, pointing out bird species on the river and introducing us to the locals. In a previous life, Noah owned a store in Washington, D.C., until a robber shot him and he was left for dead. After that near-death experience, he returned to his quiet Nile River village to live out the rest of his years.

A young mother named Fatima shared her story with us, how she chose to leave Cairo, where she had a university degree and a professional job, to raise her children here surrounded by family, in a natural setting far from the headaches of modern life. No supermarkets, modern transportation, or city bustle way out here, but excellent kid raising vibes, no doubt.

In my last post I’ll get to the actual end of the trip, finally, two more temples and the last Egyptian pharaoh, the infamous Cleopatra – she was sooooo interesting. And the crucial question….. How safe was it, traveling in Egypt? How was the Covid situation? Did anyone on our trip catch Covid? (No, but there was some drama at the end…..)

For now, let’s just say Egypt seemed way safer than Key West, where Duval Street debauchery seems to have reverted to its former level of mayhem….

Thank everyone, as always, for following along!