The Golden Triangle: Burma, Laos, Hill Tribes, and My First World Assumptions

We were sitting on red ants.

We had crossed the border into Laos, and at the local market children had been trailing our

every move, pestering us: “Baht! baht!” – imploring us to give them money, pointing to our Diet Coke cans, asking us to buy some for them (we think that’s what they wanted, anyway). As hard as it is for both of us to say ‘no’ when asked to help (especially when the askers are children), we listened when our guide Ranee told us that if we gave in, we’d cause a mini-riot among the poor children. So we hardened ourselves and kept saying ‘no’.

But now the children were frantically pointing at the stone bench we were sitting on, and not saying ‘baht’ – they were saying something else. It finally dawned on us – they were trying to tell us we were sitting on ants! We leaped

up and away, and turned to thank the children.

Who promptly resumed asking us for bahts and Diet Cokes.

When Western tourists like us visit areas of poverty anywhere in the world, we can’t help but face uncomfortable issues. I can’t stop myself, for instance, from thinking “why aren’t you in school?” and “where are your parents?” (what teacher doesn’t think that?) when I see children as young as four or five begging in the streets. And then I chastise myself for such judgmental thinking, wrestling internally with all the complicated issues that poverty raises for First World tourists like us.

We crossed the border into Burma (Myanmar) at Mae Sai, for a tuk tuk tour of the Burma

border town. Our guide Ranee grew up close by, and took us to the home of an old friend, a lame man who cooked oxtail soup and beef bones to survive. That’s how he made his living, sitting in his dirt-floor hut, cooking all day on his improvised clay stovepipe pots. He received no social services, no support. I wanted to demand “where is DSHS?” as I once again wrestled with my First World assumptions about how the world should work.

The border town we visited is part of the infamous Golden Triangle, where the Mekong River joins three countries – Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos – and opium production flourished for many years (the CIA coined the term Golden Triangle during their battle to suppress the drug trade back in the 1950’s). Successfully curtailed until recently, the drug trade (opium and now meth too) is making a comeback, due partly to China’s growing drug addiction problems, as well as demand from First World countries like the US. And drug addiction among the Golden Triangle’s poor exacerbates the area’s poverty issues for children and everyone, of course, just as it devastates lives back in the States.

We saw signs of vibrant life here too – children at school (yay!), and this lovely young lady who so seriously applied

a local mud facial treatment to Padre’s cheeks. The market was bustling, although after I had time to think about it I cringed at the level of sanitation (First World assumptions again) – produce laid out on dirty cement floors and fish slapped on old concrete blocks. Not a plastic sanitation glove in sight anywhere, something we take for granted at our local grocery store. Heck, we get in trouble if we double-dip a Dorito back home (and rightly so). We’d never buy food that wasn’t hyper-sealed, prepped and protected from germs.

We also visited one of Northern Thailand’s many hill tribe villages near the border. We climbed into the back of small trucks to ascend the red clay roads, amid forested hills and lush green rice fields. The village we visited was set up for tourist visits, with long aisles of handicrafts laid out for us to peruse. Most of the men were gone during the day, working construction jobs in the city or working in the fields. A few men remained, carving bamboo souvenirs (we purchased a carved cup for about 70 cents).

Women weaved beautiful scarves, which they sold for a pittance, and the Karen tribe’s long-necked women posed graciously for photos, even letting tourists try on the heavy

brass bands. More discomfort on my part, due to the ‘show’ aspect of all this. Ranee helped explain how the tourist dollars help the women, especially, make income from their weaving and sewing skills.

Seven hill tribes live scattered among the remote hills on the Northern border, many refugees from Burma and China, some more isolated than others. Numerous aid organizations and religious groups help the tribes, with water pipe and sanitation projects for instance, and of course with education. The church hut (with a dirt floor) was the one place I saw signs of education; a picture of Jesus at the front, and an alphabet chart – in English – to the side, with the date for Easter – April 8th – on the chalkboard.

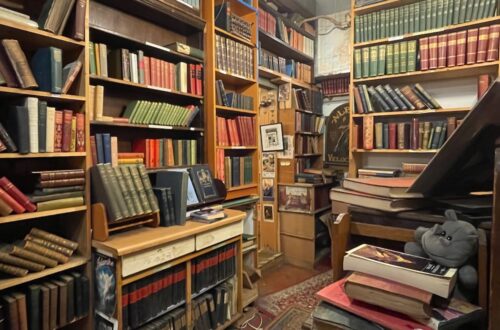

I wrestle hardest with my last assumption: Where are the books, magazines, and other signs of literacy here? I can’t imagine a world without reading (my worst nightmare/trapped in a room forever with nothing to read. Aaaaargh). So to visit a world of people and children who, if they do read, keep that activity well-hidden from the world at large – I was keeping my eye out the whole trip, in fact, and even had trouble finding a book stand at Bangkok’s large airport.

The reason this one’s so hard for me is because I so firmly believe that education is the ticket up and out for poor children in the United States. I had a discussion with a lovely woman I met on the plane to Tokyo, however, who suggested that a remote hill tribe village child might not benefit so much from the high levels of education we envision for our own children, and she had a point.

But for now, that’s one assumption too far for me, I guess – I’ll be advocating for more

education, for anyone and everyone, until I’m rocking away in the old folk’s home. And here’s my argument: Padre and I would have been able to navigate foreign life much better if we understood or could read Thai. Instead, we were dependent on our tourist helpers to translate for us. We knew, for instance, that this heart foliage display had to say something about ‘love’. But what Ranee translated for us didn’t quite fit the way we thought it did: The Thai words mean something like “Love – I’ll always miss you!.” Huh? I haven’t missed Padre for 44 days, since he’s been glued to my side and I to his on the epic journey.

And in Hong Kong, our guide Mandy attempted to teach us the several levels of intonation that affect meaning in Mandarin and Cantonese languages. You might be calling someone ‘mom’ for example, or you might be hurling a vile insult at them – same word, different intonation, only difference. And of course my failing ears couldn’t hear any difference at all, so I was probably hurling the insult. Not good.

So there you go – I plan to cling to my assumption about education to my very last day; Learning is the coolest thing ever, and everyone benefits from more learning, so there! And oh my, have we learned a lot in a few weeks! Padre

has been journaling furiously about all he’s learned (It’s encyclopedia length at this point – good luck children/he hopes you’ll read it all), and I am looking forward to finally boarding our cruise ship later this afternoon (the third leg of the epic journey) so I can start filling in all the rest of the details I haven’t had time to include so far. No travel disasters, we’re still married and speaking to each other, and of course planning the next adventure – thanks for following along, everyone!